One of the most recurrent criticisms of the European Union regarding the migration phenomenon is the quantity of migrants Europe currently receives. First, and from a very global point of view, we observe that in almost the whole of the European Union, there is an overestimation of the feeling of the migratory flow within the Union compared to its real figure. The immigrant population in the European Union is indeed perceived as 16.7% when it actually amounts to only 7.2%, i.e. less than half of the population felt[1]:

The map above shows us that this trend can be generalized to all European countries except Estonia (where perceived migration is lower than actual migration). It is also interesting to note paradoxically that, on the one hand, if there is a gap between feeling and reality, it is more narrowed within the countries that welcomed the most migrants in the 2015 wave, with Germany at the forefront with the reception of 1.5 million migrants:

On the other hand, the table above shows that among the countries where the gap between experienced and felt immigration to the European Union is wider, and more particularly in Eastern Europe, many of them have higher emigration than immigration, i.e. the outflow of migrants is higher than the inflow.

It should also be noted that illegal migration flows within the Union have fallen sharply over the past three years, i.e. since 2015, which marked an exceptional year in terms of global human mobility:

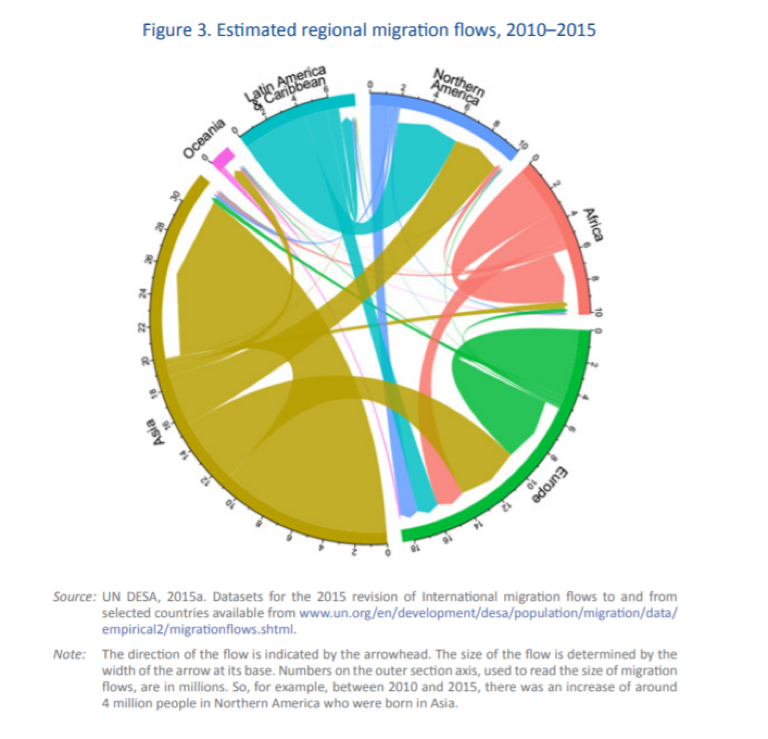

This criticism of the reception of migrants (especially African migrants) in Europe raises another question: the fear of a possible danger for European society and its culture. According to this view, Europe is invaded by migrants who initially want to benefit from Europe’s economic advantages and social laws, but also to change its traditions by not integrating. While this criticism is recurrent, it was crystallized by the meeting in Brussels on 8 December 2018 between Steve Bannon (former advisor to Donald Trump), Marine Le Pen (leader of the National Rally Party) and Tom Van Grieken (President of the far-right Flemish Party Vlaams Belang). While this idea is highly simplistic, it above all shows an ethnocentrism that ignores the reality of the global migration phenomenon. Indeed, it assumes that migrants traditionally move from developing countries known as “South” to developed countries (USA and Europe) known as “North”.[5] This assertion is by no means true, in fact, as for 2018, a report of the International Organization for Migration indicates that most of the migratory phenomena observed is not transcontinental but regional and more particularly between these so-called “southern” countries. The following table provides a more explicit understanding of the phenomenon in question for the year 2015:[6]

We can thus comfortably argue that while global migration has grown significantly in recent years with a peak in 2015, it has gradually and continuously declined since then. Moreover, Europe has been relatively spared by the masses of migrants who are unfortunately generally forced to emigrate locally or regionally, often in harsh and degrading conditions.

Zamir Sulejmani

For further information: https://www.eu-logos.org/2019/02/13/pacte-sur-la-migration-de-marrakech-2018-pomme-de-discorde-onusienne/

[1]https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/migration-eurobarometer-2018/

[2]Idem

[3]Migreurop, Atlas des Migrants en Europe – Approches critiques des politiques migratoires, Armand Colin, Paris, 2017.

[4]https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/asylum-applications-since-1990/

[5]Ligue des droits de l’Homme – Commission Etrangers, Décembre 2018, p. 2.

[6]Which was an exceptional year in terms of global migration flows.

[7]https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2018_en.pdf